On January 1, 1909, the “seat of government of the State of California shall be changed from the city of Sacramento to the town of Berkeley …” So begins the opening paragraph of a bill approved by the state Legislature in March 1907 to move the state capital. Governor James Gillett approves the measure, and the next step is to put the matter before the voters in the general election of November 1908.

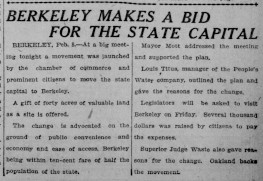

In early February 1907, Louis Titus of the Berkeley Development Company first proposes moving the capital to the East Bay at a Berkeley Chamber of Commerce meeting – to great enthusiasm.

Titus is actually president of at least nine land development companies in Berkeley, as well as manager of the People’s Water District and attorney for Berkeley National Bank.

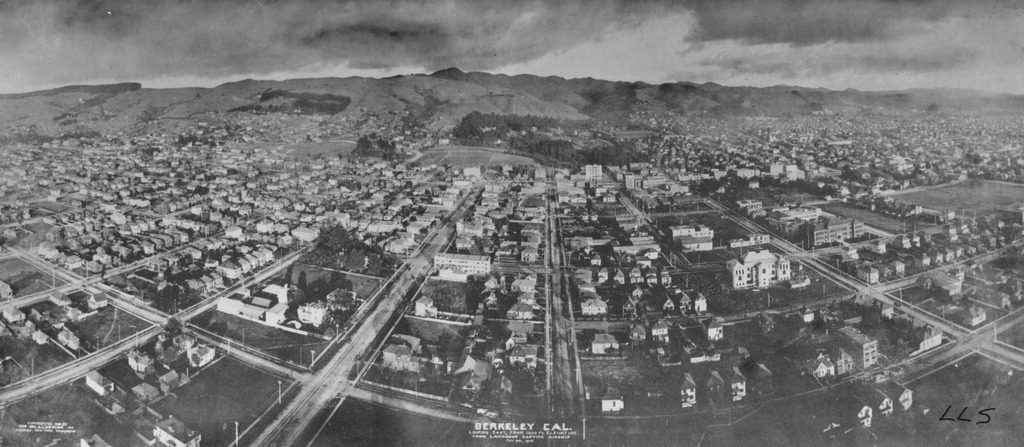

Titus offers to donate 40 acres in North Berkeley and the Berkeley Hills for the new state Capitol grounds.

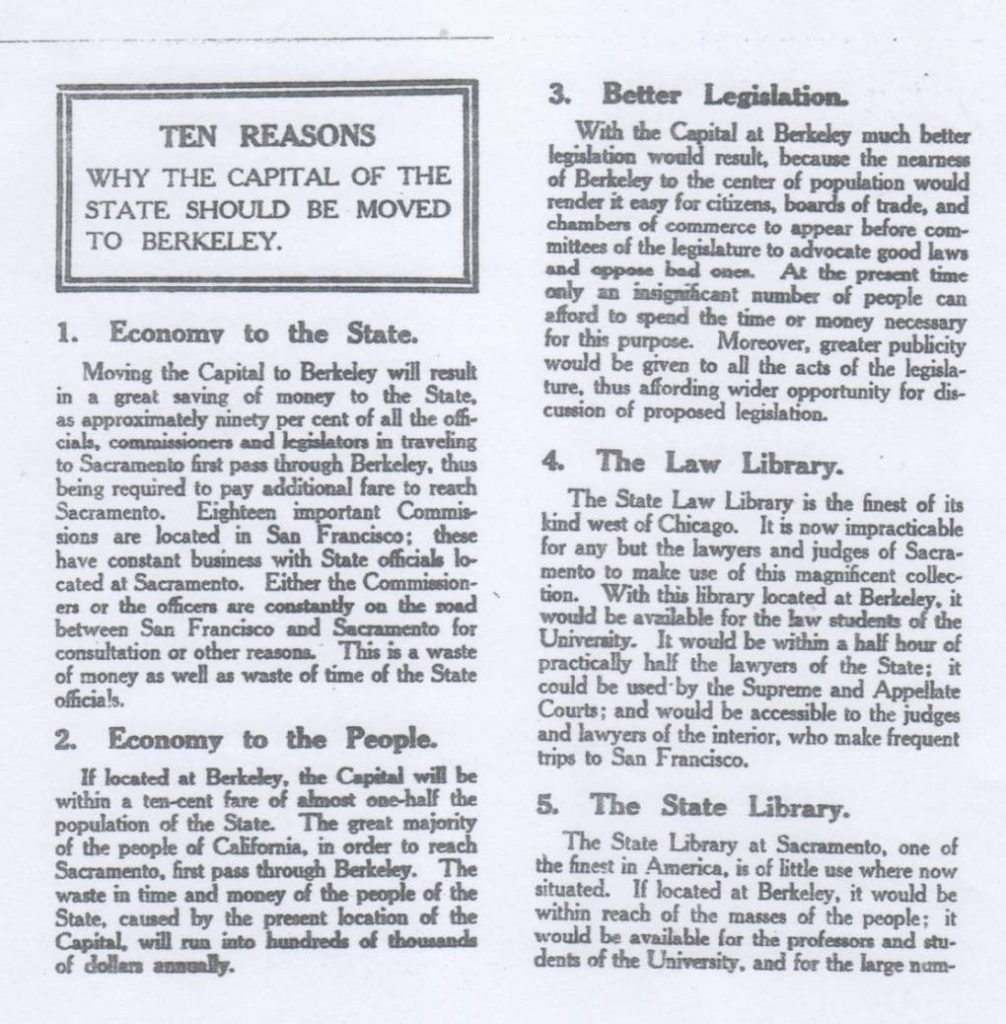

Titus argues that the great majority of Californians are not adequately served by having a state capital far removed from the general population, and relocating it to the Bay Area would save officials and legislators time and money. In 1900, about 40 percent of the state’s population lives in the Bay Area. The bay counties have 658,000 people; Sacramento County has 46,000. The pro-Berkeley forces publish “Ten Reasons” why the capital should be moved. Notably, having greater access to the State Library and State Law Library are reasons numbers 4 and 5.

There is debate over whether Titus really wants the Capitol in Berkeley or whether he’s promoting Berkeley real estate. Sacramento citizens think it’s a big joke, according to several accounts. But Titus wastes no time in getting legislators to tour the proposed site, which they do on February 23 “amid the cheers of citizens.”

Titus’ design places a circle at the approach to the Capitol site with six streets fanning outward (later to be known as Arlington Circle). There will be train service to the Oakland Pier and ferry service to San Francisco. The circle is designed by Berkeley architect John Galen Howard, designer of the Hearst Memorial Greek Theater (1903) and California Hall (1905) on the University of California campus. Howard goes on to design many of the university’s iconic buildings, including the Campanile, Doe Library, and Sather Gate.) The streets fanning out from the circle are named for California counties whose votes would be particularly welcome, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara and Marin among them.

To generate wider support for his proposition, Titus sends letters to chambers of commerce around the state, asking for their endorsement of the proposal. While some northern chambers send angry letters to the Sacramento Union newspaper denouncing the plan, others respond with tongue-in-cheek proposals, like the town of Orland, home of the orange and olive, and “why not … the state capital also.”

The editors of Los Angeles News give their less than full-throated support for keeping the capital where it is:

“We are not indorsing [sic] the Sacramento climate or praising that city as a desirable place to live, but the capital is there and there it is likely to stay.”

San Francisco Call, March 6, 1907.

The Bakersfield Californian editors may be closer to the truth of the matter for the capital staying put:

“And Berkeley is a “dry” town, too. What kind of place is that for a Legislature to meet in?”

San Francisco Call, March 23, 1907

Whether it was due to the financial panic of 1907 or the efforts of the liquor lobby and Sacramento businessmen, the proposition to move the capital fails by a large margin – with 65% of voters turning it down. Only five counties, all in the Bay Area, voted in favor.