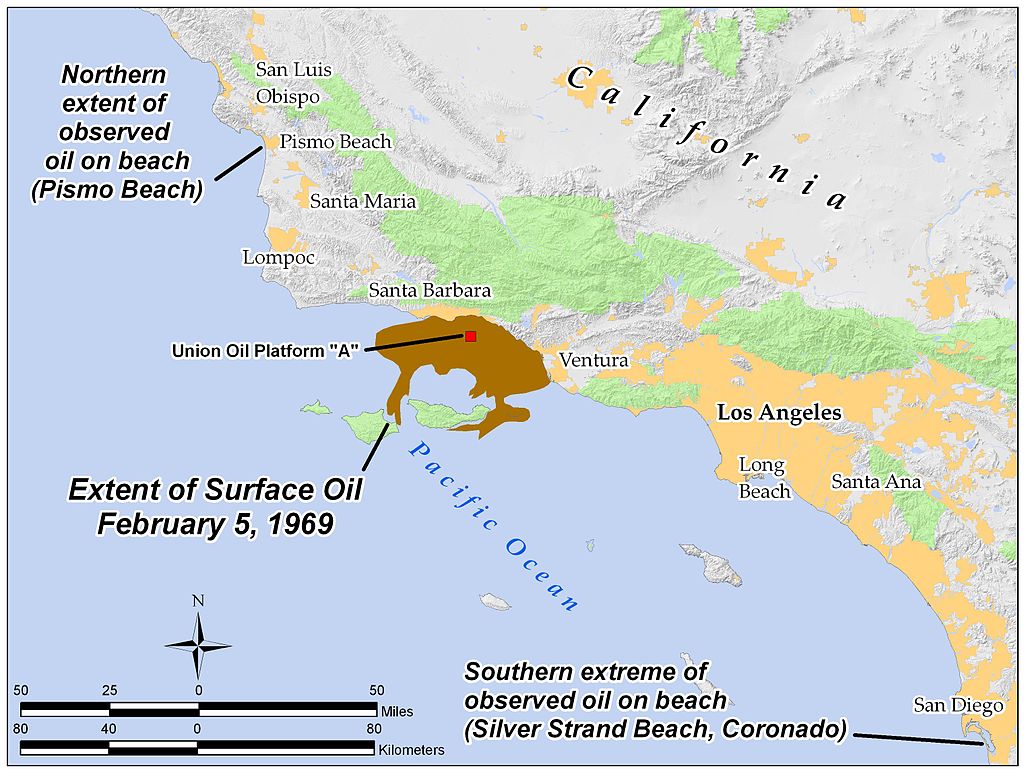

At 10:45 a.m., January 28, 1969, 5.8 miles off the coast of Summerland in Santa Barbara County, workers on Union Oil’s drilling Platform A create California’s largest oil spill. With the OK of the federal government, the oil company is using inadequate protective casing, which ruptures from the pressure of the drilling, shooting mud and crude oil skyward. Capping the well drives the pressure underground, cracking the ocean floor. Oil pours from the fissures. Union Oil initially downplays the severity of the problem but on the morning of January 29 a Coast Guard helicopter carrying a state Fish and Game warden sees 75 square miles covered by oil — less than 24 hours after the blowout.

Over the next 11 days, more than 3.3 million gallons of oil gush from drilling-induced cracks in the ocean floor. The resulting slick covers hundreds of square miles of Santa Barbara Channel waters, causes waves thick with crude oil to thump silently on the shore and coats 35 miles of beach with sludge. An estimated 3,600 birds and numerous fish, seals and dolphins die. Union Oil and thousands of volunteers struggle to stop the leak and then clean up the mess. Kenneth Clarke and Jeffrey Hemphill write in their 2002 The Santa Barbara Oil Spill, A Retrospective:

“The damage was so intense and extensive that people of all age groups and political persuasions felt compelled to help in every way they could. On the beaches, piles of straw were used to absorb oil that washed on shore, contaminated beach sand was bulldozed into piles and trucked away. Skimmer ships gathered oil from the ocean surface, and volunteers rescued and cleaned tarred seabirds at a series of hastily set-up animal rescue stations, one of which was located at the Santa Barbara zoo.”

The spill closes commercial fishing in the area until April 1970. Beaches don’t reopen until June 1. Cleanup costs exceed $4.5 million in 1969 dollars. Although Union Oil pays $9.5 million to Santa Barbara and the state, their handling of the spill and its aftermath wins no public relations awards. Union Oil President Fred L. Hartley is quoted saying he’s “amazed at the publicity for the loss of a few birds.” Richard Nixon, the first native Californian to become president, holds the office for nine days when the spill occurs. Walter Hickel, Nixon’s Secretary of the Interior, accepts some of the blame for the spill. On February 11, Nixon issues a statement saying:

“I have today directed the President’s Science Adviser … to bring together at the earliest possible time a panel of scientists and engineers. They will recommend to me ways and means in which the Federal Government can best and most rapidly assist in restoring the beaches and waters around Santa Barbara. They will also submit their views as to how best to prevent this kind of sudden and massive oil pollution.”

Nixon tours the disaster site on March 21 and, with a strong bit of political prescience, tells reporters: “It is sad that it was necessary that Santa Barbara should be the example that had to bring it to the attention of the American people. What is involved is the use of our resources of the sea and of the land in a more effective way and with more concern for preserving the beauty and the natural resources that are so important to any kind of society that we want for the future. The Santa Barbara incident has frankly touched the conscience of the American people.”

The marine life deaths, the fouled beaches and the subsequent cleanup efforts appear in living color on TV screens around the country. Coupled with a stretch of Ohio’s Cuyahoga River bursting into flame from the concentration of pollutants on June 22, 1969, the Santa Barbara spill jumpstarts the nascent environmental movement, leading to Earth Day in May 1970, creation of the federal Environmental Protection Agency and a raft of far-reaching legislation including California’s Environmental Quality Act and the federal Environmental Protection Act. A 1972 initiative creates California’s Coastal Commission.