At 11:58 p.m. on March 12, 1928, the worst dam failure in state history unleashes a wall of water between 80 and 140 feet high that surges down San Francisquito Canyon northeast of Santa Clarita in Southern California. More than five hours and 56 miles later, the 12 billion gallons of water released by the dam flow into the Pacific. But not before the town of Castaic is “swept clean as a pool table,” according to one description. A Southern California Edison construction camp is washed away, drowning 84 of 150 workers.

Parts of Fillmore, Piru, Santa Paula and Saticoy are demolished. The death toll is estimated at 600. Thousands are homeless. Almost 24,000 acres of land are washed away, some 900 buildings destroyed. Los Angeles pays $7 million in restitution to victims.

In Santa Paula, night telephone operator Louise Gipe risks her life to stay and telephone residents. California Highway Patrolman Thornton Edwards goes door-to-door rousing residents to evacuate. He becomes known as the “Paul Revere of the St. Francis Flood.”

The disaster occurs five days after the dam reaches full capacity and almost exactly three years from when construction began on March 9, 1925. It costs the Los Angeles Bureau of Water Works and Supply – forerunner of the Department of Water and Power – $1.25 million to construct the dam, which is filled with 38,000 acre-feet of water from the Los Angeles Aqueduct.

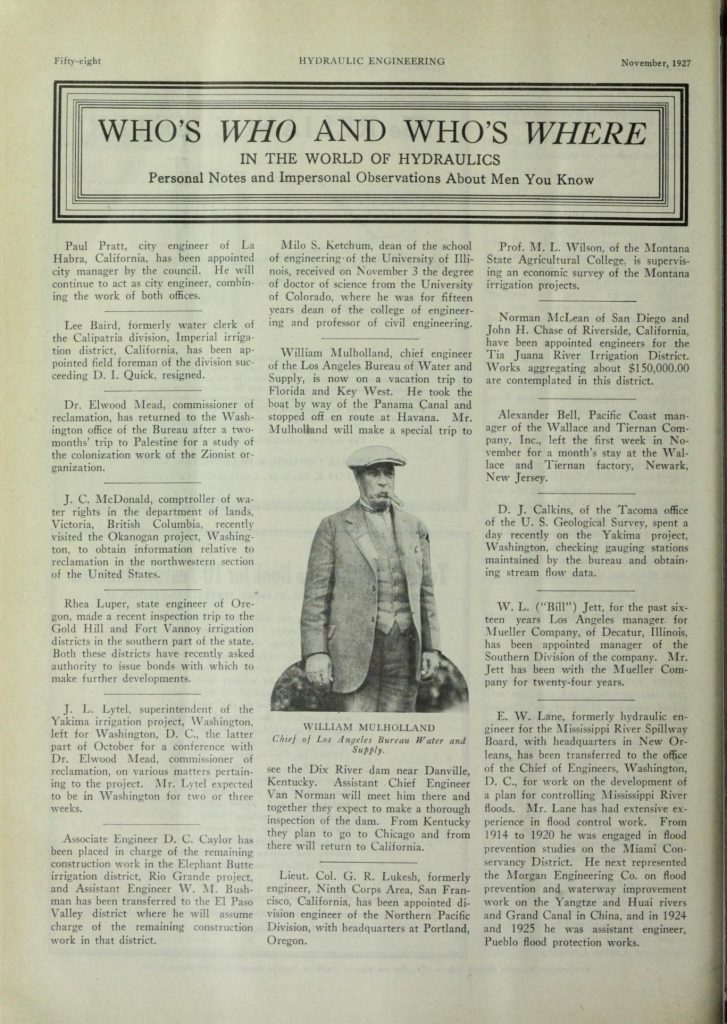

Initially, the dam is designed to hold 30,000 acre-feet (one acre-foot is roughly the water a family of four uses annually) but after construction begins William Mulholland, the bureau’s chief engineer, increases the dam’s height to boost storage capacity. He does so without sufficiently widening the dam’s base. The dam’s site, one of several considered, is the scene of an ancient landslide. The ground at the eastern end of St. Francis dam remains unstable. It’s the principal cause of the disaster but a condition that geologists of the time cannot detect. Although Mulholland is not charged with culpability he says:

“I envy those that were killed. Don’t blame anyone else; you just fasten it on me. If there was an error in human judgment, I was the human.”

The media is happy to accommodate Mulholland, particularly after he admits inspecting the dam personally 12 hours before its collapse. Early on March 12, dam keeper Tony Harnischfeger tells Mulholland that muddy water appears to be flowing from a crack at the bottom of the dam. Mulholland and his assistant engineer, Harvey Van Norman, investigate but decide the water is being muddied by construction of a new access road.

Mulholland receives a second call from the maintenance engineer at one of the dam’s hydropower generators. He too sees muddy water that seems to come from underneath the dam running by the powerhouse. Mulholland inspects the second leak and is concerned but not enough to raise an alarm.

After the catastrophe, Mulholland is never the same. He retires in November, living in near-seclusion for the remaining seven years of his life.

Gov. C.C. Young appoints a commission to investigate the disaster. Commission members tour the disaster scene on March 19 and issue a report five days later. “Defective foundations” is the cause of the dam’s failure, the commission concludes. Future dams should be built and maintained by the state, the commission adds.

The St. Francis dam’s collapse delays federal approval of Hoover Dam – and leads to it being moved from Boulder Canyon to Black Canyon, its present location. Safety inspections are conducted of other California dams and legislation passes in 1929 setting tighter construction standards – the same legislation lawmakers use as a model after the Long Beach earthquake four years later to create design and safety requirements for new school construction.