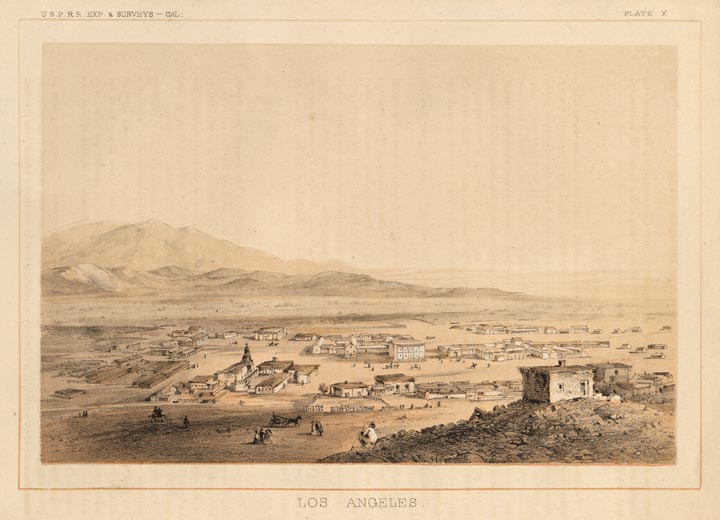

The year is 1852. It is a fine spring day in Los Angeles. A small black mare and her rider stand beside a tall roan ridden by a large Mexican vaquero. Following the roan are several other horses and riders carrying small whips. The pole for the turning point in the race that is about to be run is so distant it’s almost out of sight, obscured by the mustard waving along the dirt road. The crowd stops shouting bets at one another and now stare at the mare’s rider, whispering and chattering as if they’ve never seen a Black man before. Now comes the starting cry — “Santiago!” — and the horses leap forward. The race is on.

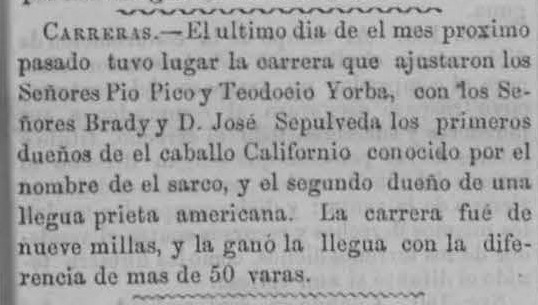

The race between Pío Pico’s California champion, Sarco, and Jose Sepúlveda’s Australian thoroughbred, Black Swan, is easily the most talked about race in California during 1852. Its genesis is an open challenge. Around 1851, Pío Pico, a prominent Los Angeles landowner and former governor, issues a standing challenge to race his horse, the undefeated Sarco, against any other animal. Jose Sepúlveda, another Southern California landowner and friendly rival, searches for a steed that can match Sarco and possibly beat him. He finds one in Northern California, Black Swan.

Black Swan Is a thoroughbred mare imported from Australia by a Mr. Turner in 1851. She has run a couple races in Northern California prior to starting her long ride to Southern California in late 1851 or early 1852 at Sepúlveda’s request. By the time she and her rider and trainer Bill Brady, arrive at Sepúlveda’s ranch in Orange County, she is exhausted.

Undeterred, Sepúlveda and Brady began conditioning her for a race against Sarco set three months hence, in March 1852. The betting also starts. Sepúlveda and Pío Pico agree to a stake of $2,000 and 1,000 head cattle, a fortune at the time. While the betting and race buildup goes on, Black Swan continues to train and slowly recovers her stamina. Ascension, Jose Sepúlveda’s daughter, rides the horse at least a few times and meets Thomas Mott, her future husband, while doing so. One of Sepúlveda’s other daughters, Tranquillina, says that while several of her father’s workmen train with the horse, only one really clicks with the animal, a young Black man.

On March 21, 1852, thousands gather to watch the big race. Last-minute betting, fueled in part by Thomas Mott and Maria Sepúlveda, reaches a fever pitch. According to his grandson, Pedro Carrillo wagers his entire life savings on Sarco. One newspaper reports that an itinerant doctor bets everything including his hat on Black Swan.

Overall, almost $50,000 is stacked on the results of this race.

Now, the jockeys mount up. Leo Carrillo recounts the shock of the spectators as they see Black Swan’s rider. No one present has seen an Black jockey before.

As is typical of the time, Sarco and his jockey are surrounded by outriders whose job is to whip Sarco forward. Black Swan and her jockey stand alone.

At the cry of “Santiago,” the horses are off. They race towards the turning point, a pole about 4 ½ miles away where a groom waits. Black Swan easily pulls ahead of Sarco in the first leg of the race but loses ground at the turning point. Some accounts say she gets the bit in her teeth, blows past the pole, and keeps going. Others say the quick face wash, mouth check and sip of water offered by the groom sets her back.

But all accounts agree that by the time Black Swan is ready to start the second half of the race, Sarco and his outriders are well ahead. And then, encouraged by a single quick slap, Black Swan runs her heart out for her jockey.

The crowd erupts as Black Swan and her extraordinary rider crosses the finish line several yards ahead of Sarco and staggers to a stop. An ecstatic Jose Sepúlveda pulls Black Swan’s saddle off and declares that she will never race again. Maria Sepúlveda drapes her shawl over the heaving animal’s shoulders. Pedro Carrillo, devastated at his loss, declares he will never gamble again. The race and its astonishing results are reported as far away as Sydney, Australia.

Though the race has a fairy tale ending, the lives of its participants do not end so happily. Black Swan retires to Sepúlveda’s ranch, where she lives a life of ease until 1860, when she dies prematurely of tetanus poisoning.

Both Sepúlveda and Pico win and lose other horse races. Eventually they both lose their ranchos and die broke.

What becomes of Black Swan’s jockey? Details of his life are scant. Later accounts of the race muddy the trail by suggesting that he is Australian, or English or, in some retellings, Jose Sepúlveda himself.

State Library research, however, can at least provide the jockey’s name. According to an 1882 summary of the race, Black Swan’s jockey is named Alexander Marshall, the first known Black jockey in California. Featured image: Los Angeles Star. April 3, 1852, pg. 3 California Digital Newspaper Collection, Center for Bibliographic Studies and Research, University of California, Riverside, <http://cdnc.ucr.edu>.