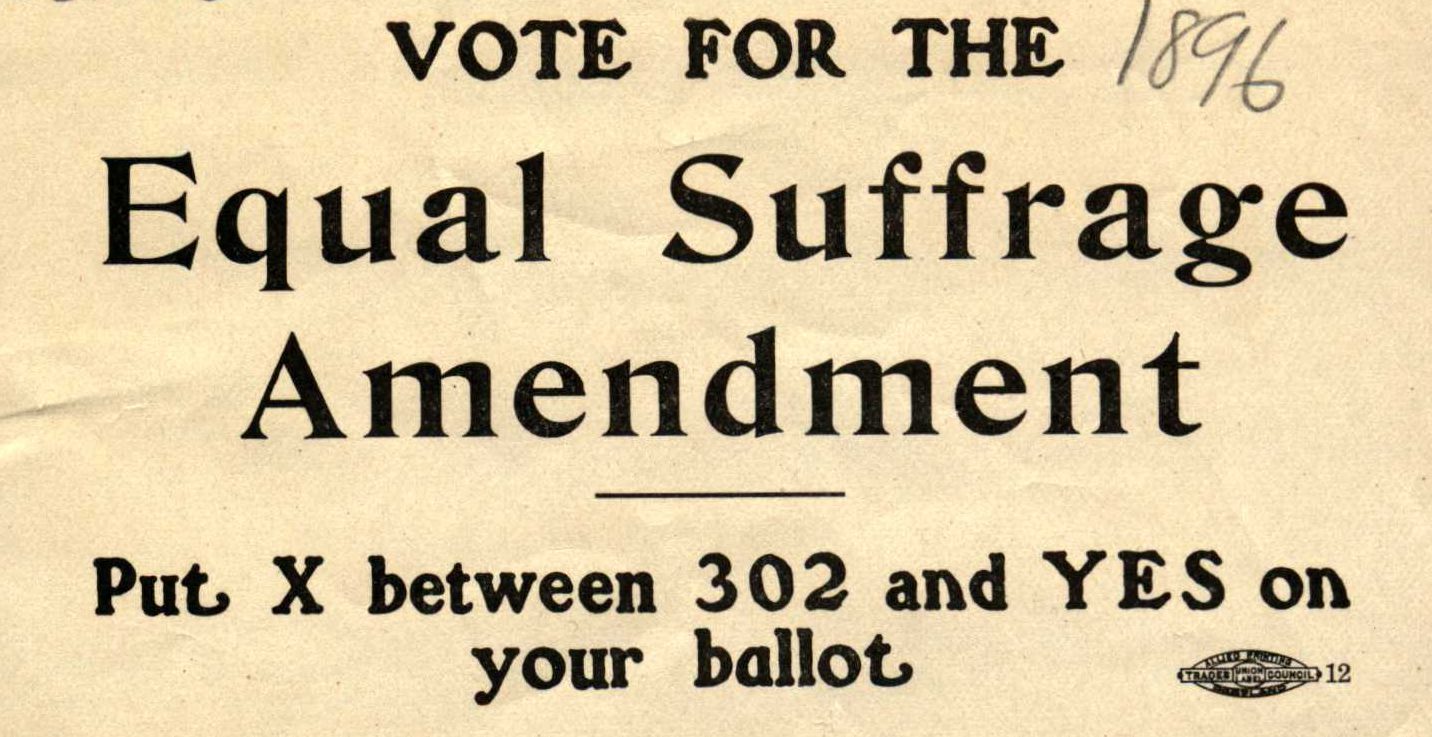

After California’s male voters decisively defeat a women’s voting rights ballot measure in 1896, suffragists display plenty of public bravado.

But it’s all for show.

The morale within the state’s suffrage movement has been crushed. Activists are weary of fighting the same battles in the Legislature every two years without result.

Despite the seeming hopelessness, a handful of indefatigable women start to slowly and methodically rebuild the movement to carry the fight to give women the vote into the 20th Century.

Much of the credit for the rebirth goes to Berkeley’s Mary McHenry Keith, the first woman to graduate from Hastings School of Law.

After a brief law career, she turns her full attention to suffrage and other issues of female political equality. She and her husband, William Keith, are personal friends of Susan B. Anthony.

One of Mary’s former classmates at the University of California, Oakland Mayor George Pardee, seeks the Republican nomination for governor in 1898 and sends a letter to Mary’s husband, noted artist William Keith, asking for his endorsement. The formal response comes not from William but from Mary.

There are no niceties in her response. She makes no mention of their four years together as classmates. She indicates that her husband might choose to offer his support, but “before permitting him to do so, I should like to ask, ‘What are your views upon the question of suffrage for women? If elected Governor would you do all in your power to enfranchise the women of your State?’ ”

Pardee loses the governorship that year, but wins the job four years later. In his lengthy inaugural address, he outlines a wide-ranging list of priorities. Woman suffrage isn’t one of them.

Meanwhile, Mary McHenry Keith revs herself into a one-woman dynamo. She lectures frequently, petitions the Legislature and recruits new members for the moribund state suffrage association. Its membership doubles between 1900 and 1901.

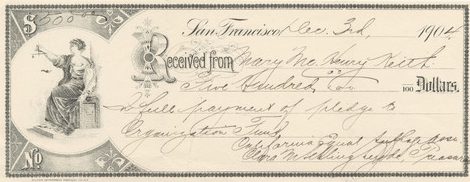

At the state association’s 1904 convention, the treasurer makes an urgent plea for donations to pay $300 in bills. Without hesitation, Keith pledges $500. After sustained applause, convention delegates rummage through their purses and offer what they can – eventually raising more than $1,100.

But legislators and political parties continue to turn their backs on the women. In 1908, frustrated and angry, Keith exhorts suffragists to agitate continuously for the vote:

“[I]s there not something in the Bible about the kingdom of heaven being taken by violence?”

In the breakthrough 1911 election that authorizes woman suffrage, the campaign sets a record for volume of posters, circulars and other propaganda. A key strategy is to send public speakers to every city, town and hamlet with at least 200 residents. It’s a struggle scraping together the funds to pay for such campaign activities, including railroad expenses for speakers who come from the east.

Eight weeks before Election Day, Mary Keith fills the campaign treasury with a $3,000 check – the equivalent of about $80,000 today – and the women win a narrow statewide victory by 3,500 votes.

There are dozens of heroines during the 42-year movement to secure voting rights for women in California. But no one contributes more to the final victory than Mary McHenry Keith, Berkeley’s “Mother of Suffrage.”

______

Steve and Susie Swatt are coauthors of Paving the Way: Women’s Struggle for Political Equality in California.